In an age of information overload, it’s hard to keep up with everything happening in the world. Information literacy is more important than ever before. Knowing where to look for information, how to decipher meaning, who to trust, and what to do with conflicting and complex information is a challenge. Those who lack the financial or technological means to keep up with an ever-changing world are at an even greater disadvantage, whether it’s an organization that can’t afford R&D costs to improve their ROI or a person without access to the internet or devices.

As well, truth (or at least credible information) isn’t something to be taken for granted anymore. While we once used to be able to assume the information consumed was credible, it’s now nearly impossible to even keep up with what’s going on, never mind make sense of it all.

In our hands is a paradox: we have more information at our fingertips than ever before, but so much information we don’t know what to do with it all. And the information we do have? Biased, messy, and inconsistent.

I’ve written previously that I don’t believe information is just a piece of knowledge. It’s an act that requires intentionality & thought, an act that requires an understanding of context, audience, and meaning-making. Information, and how we process that information is incredibly influential on how we behave & interact with the world around us.

As a result, as a new professional in the field of information (and one with the privilege of working in the social innovation space), I know the responsibility that comes with designing and presenting information. What I present, and how I present it, has a profound impact on people’s lives — at both individual and system-level scales. So, how do we go about informing people in a responsible way? How can we use information to educate and empower?

Many Meanings

At HelpSeeker, a B-Corp, we work at the intersection of social and technological innovation, focusing on digital services and solutions for the world’s social challenges and accelerating the social change needed to achieve equitable wellbeing for all. We do this by providing social-purpose technology solutions to help-seekers, service providers, and decision-makers in the social sector.

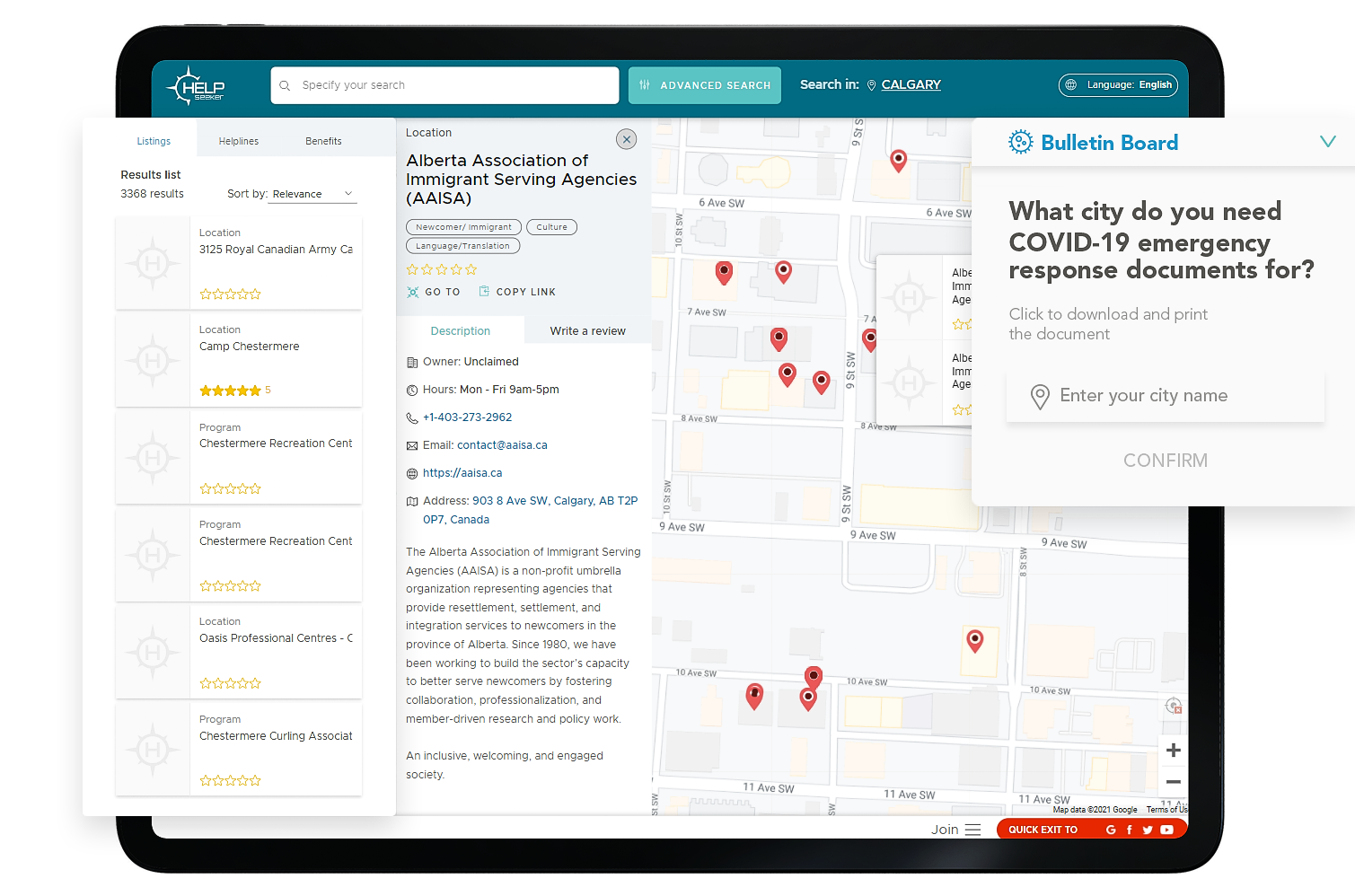

At HelpSeeker, one of our strengths is our systems map: we have a dynamic inventory of over 70,000 community & social services across Canada. As the first of its kind, this is an incredible resource. We take this increasing number of service listings and use it in two ways: to help people find the support they need (through navigation apps and helpseeker.org) and using it in combination with other datasets for systems planning purposes (Community Success Hub).

But, like any database, our inventory means next to nothing if we can’t translate it into something meaningful.

The first step to creating meaning in our data is by qualitatively coding or “tagging” each entry in the inventory. While this seems like a fairly simple concept, it’s actually a very nuanced task. By applying tags to the data, we are applying language and concepts that allow us to gather meaning from the thousands of rows of information so that it can be used to benefit help-seekers, service providers, and decision-makers.

However, the problem of taxonomy development is the same as that of language: meaning is subjective to the viewer. As a result, typology and the classification of objects is a complex process.

A classic example of this fundamental problem is the varied meaning around the term, apple. When you think of an apple do you think of a round red fruit? Or do you think of an iPhone? If it is a fruit, what makes it different from an orange or pear? And if we see a picture of an apple, is it still an apple? It’s easy to see how quickly things get convoluted.

As a society, we have come to conceptualize and group things in a certain way (and often conflicting or inconsistent ways). So in order to minimize discrepancy, we are constantly reiterating our taxonomy development process for the tags we apply to our listings. Questions we ask when developing our classification schemes are:

- What does this term mean to us? To people looking for help?

- What is the relationship between these terms?

- What other terms overlap with this term?

- What is the purpose of putting something in a category with this term? Is describing a service this way helpful or harmful?

I’ll give an example. Suppose there was a service that was tagged as “housing.” To a person with stable housing, this might indicate the service connects you with a single-family house. To a person without stable housing, it could simply mean a place to stay for the night in cold weather. Both services, in a sense, are related to “housing,” but they are very different offerings. There are also several other different types of “housing” such as supportive housing, transitional housing, and emergency housing (ex. shelters).

For some people, it’s less about the “housing” itself and more about a home (connection to land, place, people). If we take the terms “housing” and “home” do they mean the same thing here? Are all houses homes? Are all homes houses? Finally, if these things are different enough to distinguish, how would they show up when we look at the data? Is it a meaningful enough distinction to make, and will it really help decision makers? Does the distinction between a house, shelter, and home matter to someone trying to make it through the night?

With Data Comes Power, With Power Comes Responsibility

On one hand, at HelpSeeker we’re faced with immense responsibility. We need to make sure we communicate and inform in an ethical way: right from the guidelines on how we structure our data to the ways we present, design, and tell stories with it. Below, I’ve outlined a few principles we use when we gather & code our data.

Clarity, Truth & Access

Some of the most powerful things we can do to ensure our taxonomy development method is ethical are to strive for clarity, accessibility, & truth.

Clarity

Clarity is about minimizing ambiguity. The first thing we do to reduce ambiguity is select the most powerful information to pull from (in other words, we define our data fields). Then, when we fill in those fields, we do so with a systematic method (data architecture) using pre-defined definitions and protocols for language and design.

Having this consistency in structure is not only important for working with the data in analysis & data science, but also reduces the difficulty of making sense of it for viewers. By breaking down the information into parts, and then keeping those parts consistent in structure, we significantly reduce the cognitive load for the viewer. They know what to expect, how to decipher it, and can more easily identify the information most relevant to them.

Access

Accessibility refers to how simple it is to use & digest the information. There are many barriers to accessing information: cost, medium, time needed to consume, and volume are just a few of the many factors that contribute to information inequality. Part of access is making things clear & digestible, but part of access is also making things available and easy to get a hold of in the first place.

To address some of these concerns, we try to make our systems map as low-barrier as possible. The map is available & free to use for anyone with access to a device, and service providers can pull print reports of services in a given area to distribute. Improvements are underway to improve the user interface & search experience for people with disabilities.

Further, we ensure our services like technical support, consulting, training, and learning opportunities are available at a low cost to a sector with already limited resources. Raising awareness of what resources people have available to them is key, as is engaging & educating communities on data literacy, social issues, and scaling innovation. By providing easy access to this information, we empower self-determination for help-seekers, service providers, and decision-makers.

Truth

Just as much as we focus on removing ambiguity and striving for clarity, we still need to make sure we don’t lose a sense of the complexity of the community and social service landscape. This means that we need to ensure our database is comprehensive & disaggregated for factors that we know are heavily influential on our society.

Comprehensive: We map the full spectrum of services related to wellbeing. We collect not only basic information (service & contact), but also extra information such as what to expect when accessing a service, population target, and other factors. We collect as much information as we can to make understanding a service easy, as well as tell the whole story of community & social services across Canada.

Disaggregated for Intersectional Analysis: We know that historically, many groups have been overlooked in data collection. For example, data about minorities can be lumped into general population data, or data can be collected in a way that systematically excludes certain populations. As a result, we don’t have a good sense of how social issues impact under-served populations. Therefore, rather than just telling a story that is comfortable, we disaggregate our data. This means that we don’t shy away from issues, and instead tag our data to highlight differences and place emphasis on those issues by tagging with factors such as population focus & eligibility criteria, and speak openly about the causes and impacts of those issues. We also acknowledge limitations in our data transparently and talk about what those limitations mean.

Acknowledge Our Limits

The usefulness of this taxonomy has limitations. We can never perfectly meet everyone’s needs, nor can we solve issues. What we can do though, is learn, respond, and come as close as we can to an ideal solution. We know that representation is powerful, and are aware that our voice shouldn’t be the only one heard. Therefore, we do work to empower voice & self-determination for service providers represented in our inventory and use technology to constantly learn & improve our products to improve the efficacy of the method.

Empower Voice & Self-Representation

We also know that the people who run, and use, services, are the best suited to describe them. Therefore, rather than speaking for service providers, we use their own language (through open data) and let them manage the identification of their services in our inventory. We never assume how a service should be represented, and always make sure that the service provider has the opportunity to express their own voice. We also work with First Nations to ensure that their services are represented as they wish in the database. By using this conceptual approach, our resulting taxonomy becomes more inclusive and better represents the services listed in our database.

Constant Learning & Improvement

Like all people and organizations, we are limited in our ability to perfectly meet everyone’s needs. We know that the ways we use language, and the ways other people use language, likely differ. As a result, we use natural language processing to constantly learn from people’s help-seeking behaviour and actively improve our products and knowledge base. This becomes particularly important to ensure we are not excluding anyone based on characteristics such as language, background, or education level.

Tell a Compelling Story

Finally, as holders of rich data, we have a responsibility to use that data and tell a story about the system and mobilize change.

Stories About Systems

As we collect this data, we use it to answer questions. Some questions are simpler than others, such as figuring out what services exist and what those services do, but others are more complex. What do those numbers mean? What trends are there over time? By supplementing our data with other publicly available datasets, community-specific context, and subject matter expertise, we are able to put together a compelling story about the health of the system — not only in terms of services, but also the structures and behaviours that hold the current system in place, and the impact of the system on individuals’ lives.

Using Information to Mobilize Change

Because we have such rich data and stories to share, we do our best to use that data for social good. First, we publicly make our database available to people seeking help, so that they have a complete menu of options available to them. Second, the stories in our data are available and accessible to people in positions of power, such as service providers, governments, and funders of social services. This real-time information, grounded in research & evidence, is incredibly valuable in terms of mobilizing system-level change. The data & stories we present not only become a justification to re-evaluate how we approach serving the community, but also the foundation for community stakeholders to come together around complex social issues with a common understanding. Our offering is not just data, but the grounds from which communities can convene to facilitate systems change and advance equitable outcomes.

Conclusion

The power in working with data is not something to be taken for granted — especially when that information has the power to affect people’s livelihoods. Especially in a world where information is overwhelming us, working with this data, making sense of it, and representing a story is a job that requires intention, responsibility & humility. We need to ensure, now more than ever, that the stories we tell to the world are clear, truthful, and compelling, and that they are being shared where it matters the most.

Interested in learning more about me or my work at HelpSeeker?

Please feel free to reach out to me [email protected] or visit helpseeker.co to book a consultation.

Click here if you’re interested in participating in upcoming design labs.