Across Canada, community change-makers are faced with the challenge of right-sizing the social infrastructure in their municipalities, searching for ways to improve both its efficiency and effectiveness. Understanding how funds flow into the different supports, who the primary funders are, how the funds are distributed – this all affects a community’s ability to create correct, efficient, accessible and equitable supports. In turn, this is how a community can overcome the challenges of complex social issues.

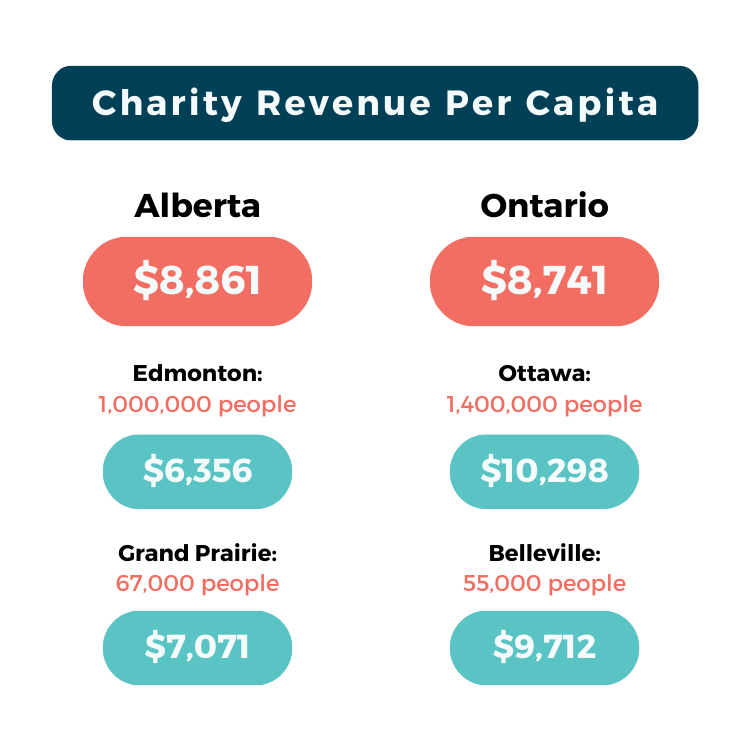

Overall, Canadian charities see about $284 billion in revenues – 67% of it coming from taxpayers via government contracts or grants. Looking specifically at Ontario and Alberta, the per capita charity revenue in Alberta sits at $8,800, which is comparable to Ontario at $8,700. However, within these provinces, there is a vast disparity between population centres. We can see divergent capital spending when comparing Belleville and Ottawa in Ontario, and Edmonton and Grande Prairie in Alberta.

We can see the population disparity across these cities shows an inequitable distribution of charity revenues per capita. Complex social issues are often caused by a misalignment of supply and demand — too many or too few social supports to meet the wellbeing needs of a community.

This begs the question: are there notable discrepancies in capacity across issue areas, spatial parameters, and demographics served? More importantly, how are these funding decisions made? And what are the driving forces that dictate where funding flows?

How Do We Find the Right Fit?

This misalignment of funding has led to an ecosystem of support that does not match demand. So how do we optimize our system and redirect funding where it matters most? The first step in optimizing social infrastructure is to better understand the entire ecosystem of supports; this includes how and by whom they are funded.

Supply mapping offers a conceptual map of the existing social response, including service and program frequency, populations served, unique attributes within the social response, program costs, capacity and common information and referral pathways. Supply mapping offers a road map to right-sizing the social infrastructure of a community and empowering its change-makers to enact change at all levels of government and with funders.

In British Columbia, seniors make up 13.3% of the population. Data shows that just 18% of services available are targeted to seniors. In the short term, this may seem equitable for the population. However, British Columbia has a fast-growing senior population, and by 2038, it is expected to have an aging population between 24-27%. Without building a roadmap to optimizing funding in our social safety net, we won’t be able to meet the demand of growing and shifting populations. Understanding how demographics will change is critical to understanding the senior-serving sector’s projected capacity.

Right-Sizing Supports. Optimizing Community Wellbeing.

How can we leverage supply mapping to transform social infrastructure? HelpSeeker uses supply mapping to provide a deep look at the social response, help measure demand for social supports, and inform new social infrastructure investment models. We examine funding from different levels of government, systems players, private funders and individual donors to understand the services and financial assets that already exist to prevent misalignment of supply and demand. Through this, we can identify variances across social supports to right-size the wellbeing needs of a community.

Finding the Right Fit: Supply Mapping for Your Community

Right-sizing your community’s social infrastructure requires an extensive supply map that is then analyzed, disseminated and interpreted to realign supply and demand to meet the needs of your community.

Supply mapping examines all of the service delivery actors in the local response. It takes an in-depth look at service categories and interprets how program capacity aligns with demographic needs. For example, we can look at the supply of food programs as compared to projected neighbourhood income levels. Further, we assess the overall supply and seek to uncover discrepancies within the supply map that would explain or may contribute to social disorder.

Finding the right fit requires seeking out these discrepancies in the social safety net and determining how the supply map can explain or contribute to complex social issues – and how we can solve them.